Inflation - Business in United States of America

Definition: Sustained, general increase in prices

Significance: Inflation temporarily increases business profits, but it distorts business accounting measures; drives up interest rates; augments conflicts with customers, suppliers, debtors, and creditors; and contributes to antibusiness political sentiment.

Before the twentieth century, inflation in the United States generally resulted from government issues of paper money, primarily in wartime. The dollar was linked to gold or silver, and people measured monetary imbalance by deviations between the price of precious metals on the open market and the face value of the paper currency.

Paper money issues were relatively common in the American colonies before the American Revolution. Some resulted from the operation of government loan offices. In other cases, paper money was simply issued to help finance government expenditures. Although not formally redeemable in precious metal, the paper money could be used to pay taxes and to buy government securities. Conflicts arose when debtors attempted to repay private debts originally arranged because of repayment in precious metals. Most colonies used paper money constructively, but significant price increases accompanied currency issues in Rhode Island and North Carolina.

After the American Revolution began in 1775, the Continental Congress began to issue a national paper currency, paid out to soldiers and suppliers. The Continental currency was linked to Spanish milled silver dollar coins (known colloquially as “pieces of eight”), and each specified on its face that it could be exchanged for a specific number of “Spanish milled Dollars, or the value thereof in gold or silver.” Before the end of 1776, about $25 million worth of currency had been issued, and prices were rising. By the end of 1779, an estimated 226 million had been issued. The paper currency quickly lost its value against precious metal. In October, 1778, a silver dollar was worth 5 paper dollars. It was worth 30 dollars a year later, 78 dollars in October, 1780, and 168 dollars in April, 1781. Meanwhile, state governments were issuing their own paper money. Governments attempted to fix prices, punish hoarders of goods, and make paper currency legal tender.

The Constitution of 1787 reflected a desire to avoid repetition of the coercive and confiscatory elements of revolutionary inflation. State governments were forbidden to impair the obligation of contracts or make anything but gold or silver legal tender for debts. The remaining Continental currency was accepted at a rate of one hundred to one for new, gilt-edged federal government securities created in 1790. The new federal government did not officially issue paper currency again until the U.S. Civil War. The War of 1812 brought a renewed burst of inflation, most of it resulting from extensive issue of banknotes, as banks bought war bonds from the government. Wholesale prices rose almost 50 percent from 1811 to 1814. The war’s end was followed by sharp deflation. By 1820, wholesale prices were below their 1811 levels.

Civil War Inflation

The dollar was kept more or less on a stable equivalence to precious metals until the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. The magnitude of war expenditures led both North and South to repeat the paper money experience of the revolution. In the North, federal expenditures in 1862 were six times those of the 1850’s. Rapid expansion of money resulted from bank purchases of government bonds and the creation in 1862 of a new currency—greenbacks. The federal government paid these out to soldiers, civilian workers, and suppliers. In December, 1861, banks ceased redeeming their notes in gold, and the new greenbacks were not linked to precious metals. The new currency retained value, however, in part because it could be exchanged for government bonds on which interest was paid in gold. By the time the war ended in 1865, the money supply had doubled in the North. The cost of living was 75 percent above what it had been in 1860, and wholesale prices at their peak were more than double their prewar levels.

Inflation resulting from paper-money issues was much more severe in the Confederacy. Confederate paper currency issues began in mid-1861, and by early 1862, the money supply of the Confederacy was more than double what it had been a year previous. Between October, 1861, and March, 1864, prices rose at an average rate of 10 percent per month. By 1865, prices had risen almost one hundredfold, and for a brief period there was genuine hyperinflation—that is, price increases of at least 50 percent per month. When the war ended, Confederate currency became worthless—until a collectors’ market emerged. Thereafter, prices trended steadily downward until the 1890’s, as national output grew faster than the money supply. After 1896, gold discoveries contributed to monetary growth, and prices rose again.

World War I and World War II

The Federal Reserve system came into operation in 1914, and just a few months later war broke out in Europe. As the belligerents purchased more U.S. products, U.S. price increases accelerated. The inflation process became severe when the United States entered World War I in 1917. Unlike the situation during the American Revolution and the Civil War, the Treasury did not significantly pay for its purchases with its own currency but instead paid with checking deposits created by the Federal Reserve and by commercial banks. Bank deposits grew rapidly, because the Federal Reserve loaned freely to banks, increasing their reserves and enabling them to purchase more government bonds.

Although by 1918 wholesale prices had risen to approximately double what they had been in 1913, the cost of living rose by only about 50 percent over that period. After 1918, the Federal Reserve continued to promote monetary expansion to aid the Treasury in refinancing war loans. The cost-of-living index in 1920 was at approximately double its 1913 level. Finally, in January, 1920, the Federal Reserve adopted a restrictive monetary policy. This policy quickly put an end to price increases and led instead to brief but severe deflation in 1921 and 1922.

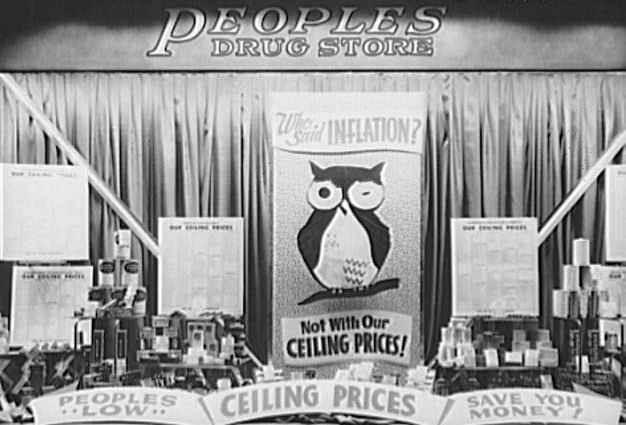

A new bout of inflation emerged as war spread across the world beginning in 1939. After the United States entered World War II in December, 1941, the Federal Reserve once again facilitated rapid expansion of money and credit to help the Treasury sell bonds. The corresponding wartime price increases were far smaller than in World War I, however, and were smaller than the proportional monetary expansion. One reason for this relatively low inflation was that the economy was still recovering from the Great Depression. Many unemployed workers and idle factories were brought back into production to meet the rising demand for wartime labor, and the wages paid to the newly employed workforce reduced the extent to which newly issued currency represented a surplus and therefore an inflationary pressure. Furthermore, people were willing to save a significant proportion of their income, anticipating that the war’s end could bring on another serious depression. Extensive controls over prices and wages were imposed, beginning in 1942.

Postwar and the 1950’s

Consumer prices in 1945, when World War II ended, were only 22 percent higher than they had been in 1941. After the wartime controls were removed in 1946, a powerful upsurge of spending by consumers and businesses triggered a new round of inflation. Consumer prices rose about 10 percent per year between 1945 and 1948. Americans began to realize that there would not be a repeat of the postwar depressions of the past.

The inflation surge ended temporarily when a mild recession in 1949 brought price reductions, but a new inflationary shock erupted with the outbreak of the Korean War in the summer of 1950. Fearing a return to wartime price controls and shortages, consumers and businesses rushed to buy goods, driving up prices by 10 percent in the first twelve months of the war. Tax rates were increased in the latter part of 1950; consequently, the federal government did not engage in large-scale deficit spending. Fiscal policy was aided by the reimposition of price controls in January, 1951.

The buying frenzy of 1950 was financed in part by borrowing from banks, leading to an expansion of money and credit aided by Federal Reserve purchases of bonds from banks. The public’s money holdings increased by $6 billion during 1950. Unhappy with this situation, Federal Reserve officials ended their commitment to support government bond prices. Interest rates were thus free to increase, and they did.

The inflation of 1942-1952 resulted from a great expansion of aggregate demand that led to a huge increase in national output, employment, wages, and consumption. Many households held savings accounts and savings bonds with very low interest rates. Inflation reduced the value of these assets, and higher nominal incomes placed many Americans in higher income-tax brackets.

With the end of hostilities in Korea in 1953, most of the government’s direct price controls were removed. Defense spending was curtailed. Prices drifted upward gradually between 1951 and 1965, as inflation averaged about 1.4 percent per year. Because of product improvements and innovations, the value of the dollar did not decrease for consumers. A steady rise in interest rates compensated creditors for higher product prices.

The Peacetime Inflation Surge

Booming business and the increased U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War escalated price increases beginning during the mid-1960’s. The government incurred substantial deficits, and the Federal Reserve expanded the money supply rapidly. Demand for goods rose more rapidly than production could expand. Unemployment declined to a very low 3.5 percent of the labor force in 1969. In 1971, President Richard M. Nixon imposed direct controls on wages and prices. Inflationary demand pressures were already slowing, as the United States withdrew from Vietnam. Congress voted in 1972 to index Social Security benefits. After 1974, these benefits increased automatically in step with rising prices, so their real value would not decrease.

The economy was rudely jolted in October, 1973, when members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) imposed a ban on shipments of petroleum to the United States. The wholesale price of crude oil rose by 27 percent during 1973. The ban was lifted in March, 1974. Largely by coincidence, most wage-price controls were removed the following month—but not those on petroleum products. While the oil crisis developed, the Federal Reserve was generating a rapid increase in the money supply in an effort to reduce unemployment. The combination of a restricted petroleum supply, higher business costs, and expanding demand drove the rate of inflation above 12 percent in 1974.

As oil supplies improved, prices of gas and oil peaked in the summer of 1974 and then slowly began to decrease. The inflation rate receded to 6 percent in 1976. Distressed by rising unemployment, Federal Reserve officials accelerated monetary expansion. This expansion in turn increased the demand for goods and services. In January, 1979, Islamic militants drove the shah of Iran from power, and the new Iranian government stopped oil exports. In two months, Iranian oil prices rose by 30 percent. The shock was quickly transmitted to the U.S. economy. By September, 1979, gasoline prices were 52 percent higher than they had been one year earlier, and heating oil prices were 73 percent higher. The general inflation rate exceeded 13 percent per year in 1979 and 1980.

Business Week commented in May, 1978, that “inflation threatens the fabric of U.S. society.” Much of this concern arose from public anxiety. Inflation generated animosity toward labor unions and businesses alike and eroded confidence in the government. The inflation of the 1970’s raised nominal wages by nearly the same percentage as it raised consumer prices, so real wages were relatively constant. Under normal circumstances, however, real wages would increase in response to rising productivity, and that did not occur.

Because price increases made people eager to borrow and reluctant to lend, they drove interest rates to unusually high levels. Rates of return on high-grade corporate bonds reached 8 percent in 1970. They fluctuated around this level, then rose to 9.6 percent in 1979 and 12 percent in 1980. Higher costs and higher tax liabilities prevented a rapid rise in corporate profits, which dampened the stock market. Stock prices rose very little from 1969 to 1979, so investors lost real buying power.

Economists struggled to interpret the experience of the 1970’s. The unemployment rate, which had averaged less than 4 percent from 1966 to 1969, hovered around 7 percent between 1975 and 1979. The term “stagflation,” signifying inflation accompanied by stagnant economic growth, came into common use. Inflation was blamed by some on wage demands of labor unions and by others on the monopoly power of big business, but the chief cause was rapid monetary growth. By 1980, economists generally agreed that market interest rates would rise point-for-point with increases in the expected inflation rate. It became clear that unexpected inflation caused much more harm than did anticipated inflation. Public discontent with inflation, high interest rates, and high unemployment all contributed to the victory of Ronald Reagan over Jimmy Carter in the presidential election of 1980.

After 1980

Encouraged by the election results of fall, 1980, Federal Reserve chief Paul Volcker took steps to reduce the growth rate of the money supply. In the short run, this put the economy through a painful economic recession. The inflation rate quickly receded, falling below 4 percent in each year from 1982 to 1986. The reduction in inflation was aided by declining world oil prices, which helped stabilize household energy prices (which shot up by 30 percent in 1980-1981) and ultimately caused them to decline by 20 percent in 1986. Energy prices were lower in 1986-1989 than they had been in 1981. The reduction in inflation seemed to validate the “monetarist” perspective, according to which inflation is a response to excessive money growth and high interest rates are a response to expectations of high inflation.

Between 1983 and 2007, consumer prices rose at an average annual rate of about 3 percent. This rate was below the public’s threshold of pain and panic. The Federal Reserve learned to keep monetary expansion under restraint. Import competition attending the increasing globalization of the U.S. economy helped hold down prices and wages. Because Social Security benefits had been indexed, beneficiaries received higher payments to offset higher living costs. Indexation was extended to the personal income tax during the early 1980’s, reducing the tendency for inflation to push people into a higher tax bracket. In 1997, the government began issuing inflation-indexed bonds.

Effects of Inflation

Most individual households are harmed by inflation. For the entire economy, however, the negative effects of inflation are questionable. Inflation is commonly the result of strong increases in the demand for goods and services, enabling businesses to obtain higher prices and stimulating greater production. The same inflation that raises product prices also tends to raise wages. When production increases, it is doubtful whether society as a whole is made worse off. When inflation is anticipated, people factor it into their decisions. Wages and interest rates are adjusted. In contrast, unanticipated inflation victimizes creditors who have made long-term commitments. Widespread indexation has reduced inflation vulnerability, partly among the elderly.

Even so, inflation tends to generate anxiety, even among people who appear objectively to benefit from it. This is because most people do not understand the sources of inflation and feel they are being victimized. Such anxiety can lead to harmful scapegoating of businesses and labor unions and to political “remedies” such as price controls that may do more harm than good.

Inflation poses problems for business accounting. Tax laws permit firms to recover tax-free the cost of capital assets, allocated over time by depreciation. However, if the prices of physical assets are rising, the depreciation allowances will not permit recovery of enough money to replace an asset.

By the early twenty-first century, the view that inflation is a result of excessive monetary expansion had become widely accepted. The Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank acted accordingly to anticipate, limit, and mitigate periods of inflation.

Paul B. Trescott

Further Reading

- “The Great Government Inflation Machine.” BusinessWeek, May 22, 1978, pp. 106-150. This “report from the battlefield” conveys a sense of the social tension and political unrest of the 1970’s.

- Mishkin, Frederick S. The Economics of Money, Banking, and Financial Markets. 7th ed. New York: Pearson/Addison Wesley, 2004. This widely used college text analyzes the relative roles of OPEC and the Federal Reserve in the inflation of 1973- 1983; also provides analysis of interest rates and foreign-exchange rates.

- “Reflections on Monetary Policy Twenty-Five Years After October, 1979.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 87, no. 2, Part 2 (March/April, 2005).Traces the recognition that inflation is primarily a result of monetary policy and the Federal Reserve’s policy adjustments in 1979.

- Sargent, Thomas J. The Conquest of American Inflation. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1999. Reviews the historical experience of inflation in the United States and how policy makers have learned from it.

- Schmukler, Nathan, and Edward Marcus, eds. Inflation Through the Ages: Economic, Social, Psychological, and Historical Aspects. New York: Brooklyn College Press, 1983. The fifty-three articles in this collection cover a breathtaking range of topics, including several on U.S. inflation.

See also: Revolutionary War; trickle-down theory; wars.

Currency: Civil War Developments

Currency: Revolutionary War and Confederation

U.S. Civil War: Confederate Finances

Federal monetary policy

Energy crisis of 1979